- Naslovna

- DRUGI SVJETSKI RAT

- Na dan ustanka u Francuskoj

- Prvi svjetski rat

- Slike moja kolekcija

- OZNAKE,MEDALJE ZA HRABROST,SABLJE

- VOJNE ODORE,KAPE

- Log pod Mangartom

- Obilježavanje bitke na Monte Meleti

- Bitka na Monte Meleti

- Vojno groblje Lebring

- Vojno groblje Amras

- Vojno groblje Pradl

- VOJNO GROBLJE Nagyharsán Mađarska

- SOLDATENFRIEDHOF KOD RETZA

- Otkrivanja spomenika vojnicima na Soškom frontu

- Kühbergl u Bruneck

- SLIKE BH REGIMENTE

- Džamija u Logu pod Mangartom

- Muzej 1915 - 1918 in Kötschach - Mauthen

- Muzej Franz Ferdinand

- Knjige WWI

- BITKA KOD CAPORETTA

- Spomenici

- Ulice Bošnjaka Graz

- Meletta Komemoracija 2015

- Zastave Bosne i Hercegovine

- ZANIMLJIVOSTI

- Neispričane priče

- Stjepan Tomašević kralj

- Katarina kraljica

- Bošnjaci dolaze

- Najodlikovaniji vojnici Monarhije

- Oduzimanje teritorije Austrije Madžarske i Njemačke

- 170.000 ih se nije vratilo kući

- Bosanski fesovi u prvom svijetskom ratu

- Sa fesom na glavi za Austro-Ugarsku

- Elez Dervišević, najmlađi vojnik Prvog svjetskog rata

- Park prijateljstva u Szigetvar

- Bošnjaci - pouzdani vojnici Austro-Ugarske Monarhije

- Jedan Bosanac, dva Bosanaca

- Čuvaju Bošnjaci

- Car Franjo, od zlata do željeza…

- Bosanske elitne jedinice u 1. svjetskom ratu

- Genocid nad njemačkom manjinom u Jugoslaviji 1944-1948

LUG POD MANGARTOM

grad u Sloveniji - oko ili 80 km sjeverozapadno od Ljubljane

Log pod Mangartom

vojno groblje iz prvog svijetskog rata (1914-1918)

BiH jedinice u I svjetskom ratu

Na prostoru BiH do 1914 godine bile su formirane 4 regimente i to:

Prva regimenta -domicil Sarajevo

Druga regimenta -domicil Banjaluka

Treca regimenta -domicil Tuzla

Cetvrta regimenta -domicil Mostar

Pocetkom rata 1915 osnovana je 5. BH regimenta, a u toku rata jos i 6., 7. i 8. regimenta

Bosansko-hercegovacke jedinice su bile rasporedjivane na frontovima sirom Austro-Ugarske monarhije. Neke od njih bile su na Galiciji, Soci, Piavi, Karpatima i regionu Alpa. Soski front je ostao

specifican zbog ogromnih zrtava koje su na njemu pale,a ciji veliki dio su nasi preci-Bosnjaci. Dobio je ime po rijeci Soci koja se nalazi u zapadnom dijelu Slovenije, na granici prema Italiji.

Bosnjacki vojnici (u to vrijeme Bosnjacima su se nazivali svi koji su bili iz BiH) su imali posebne uniforme i posebne kape-fesove. Te uniforme su poslije koristili svi vojnici koji su bili iz Bosne i Hrcegovine. Boja uniformi i fesova je bila zeleno-siva. U ratu su BH regimente i imale napadacku ulogu i smatrale su se jednim od najelitnijih dijelova austruogarske armije, zajedno sa tirolskim carskim stijelcima i nekim austro-njemackim i hrvatskim (dalmatinskim) regimentama. Bosnjaci su se pored uniformi isticali i posebnim oruzjem. Pored pusaka u borbi su rado koristili nozeve i buzdovane. U borbi prsa u prsa bili su nepobjedivi.

Od svih regimenti posebna paznja se pridaje 2. BH. regimenti koja je u toku rata dobila 42 zlatne medalje. Zlatna medalja je bila najvise odlikovanje u austrougarskoj vojsci.

2. BH regimenta je slovila za najodlikovaniju jedinicu. Odlikovanja i ordenje su inace bili u obliku raznih krizeva, dok su odlikovanja dodjeljivana Bosnjacima iz postovanja prema njima bila

posebnog oblika.

Bosnjacki vojnici zakletvu su davali nad Kur'anom, a svoje mrtve su pokopavali kao sehide. Bosnjaci su u svojim jedinicama imali imame i mujezine koji su kako se spominje i nakon povlacenja BH

jedinica ostali i pet puta dnevno ucili ezane kojima su opominjali Italijane da su jos na frontu.

Najveci uspjeh 2. BH regimente je proboj kroz italijanske linije u julu 1916 godine na Monte Melleti, koji je poslije omogucio austrougarsku pobjedu. U toj regimenti su bili oni koji uopce nisu

nosili puske, nego samo bombe i nozeve ili buzdovane. Cijena hrabrosti i odlikovanja koja su primali bila je mnostvo mrtvih.

Bitka na Kobaridu (Caporetto), inace dvanaesta i posljednja koju je dobila Austrougasrka naziva se »Cudom na Kobaridu«. Bitka je pocela 24. oktobra 1917. artiljerijskom paljbom i plinskim

granatama. Talijani su protjerani preko rijeke Tilment (Tilmento). U toj bitci je sudjelovalo 64.000 Bosnjaka i Hrvata, sto zajedno iznosi 38 bataljona. Gubici su bili nejveci za tri udarne

austrougarske divizije (1., 50. i 55.) u koje su bile ukljucene i bosanske jedinice (Bosnjaci, Hrvati i Srbi). U akciju su stupili s nedovoljnim brojem mitraljeza i slabom topnickom podrskom, sto

je bio razlog tolikom broju mrtvih. Samo 1. divizija je na kraju drugog dana borbi imala 40 mrtvih oficira i 1.550 vojnika. U operacijama od 24. 10. do 27. 11. 1917, zivote je izgubilo izmedju

3000 i 4000 Bosnjaka i Hrvata.

Od ostalih bitnijih operacija BH regimenti u 12. soskoj bitci mogu se izdvojiti:

a) 3.BH lovacki bataljon je u popodnevnim satima 24. 10. zauzeo greben Cemponov i prodro do glavne italijanske odbrambene linije na Srednjem. Sljedeci dan se sa 22. gorskom brigadom zauzeli

Globocak.

b) Bosnjaci iz 2. BH regimente su u ranim jutarnjim satima 25. 10. zauzeli Miju (Monte Mio) i nastavili napredovati prema Stupici.

c) Bosnjaci iz 1. BH regimente su zajedno sa Hrvatima i Nijemcima u krvavoj bitci savladali odbrambene jedinice u Morteglianu i Pozzuolu di Friulli. Gubici su bili ogromni, 5 oficira i 250

vojnika.

d) Bosnjaci iz 4. BH regimente su u noci između 2. i 3. novembra presli preko rijeke Tilment kod Cornina, kao prva udarna jedinica. Uprkos jakom otporu uspjeli su uspostaviti most. Zarobili su

3.000 Talijana i zaplijenili su 13 topova. Poslije su im pomoc pruzila dva bataljona iz 2. BH reg.

U dolini rijeke Soce, u Julijskim Alpama i jos na sirem podrucju su prije skoro devet decenija umirali Bosnjaci. Njih na hiljade! Danas na njih podsjecaju samo vojna groblja kojih je samo na

podrucju Slovenije na desetine. Jedno od tih grobalja je i ono u Logu pod Mangartom. U tom groblju je ukopano oko 1330 vojnika, od kojih su vecinom Bosnjaci.

Italija koja je Prvi svjetski rat okoncala kao pobjednik, a inace saveznik Srbije je nakon povlacenja kako to neki tvrde zbog mrznje koju je imali prema Bosnjacima koji su joj u toku rata

zadavali velike nevolje je srusila dzamiju. Poslije u kraljevini SHS okolnosti su bile takve da nije bilo pozeljno isticati zasluge BH regimenti protiv Talijana.

Spomenut cemo ovdje i Eleza Dervisevica, djecaka koji je sa kao cetrnaestogodisnjak postao najmladji korporal u K.und K. armiji. Nakon devetnaest mjeseci provedenih na frontu je ranjen nakon cega je lijecen u bolnici u Becu. U bolnicu mu je mahsuz u posjetu dosla nadvojvotkinja Isabelle, koja je mu je obezbjedila skolovanje i vjersku pouku pred imamom kasarne Rossauer. Elez je dobio nekoliko odlikovanja. Jedno vrijeme poslije je proveo sa majkom Muneverom i bratom Osmanom u Bosni. Umro je pocetkom devedesetih godina proslog stoljeca u Damasku. Bio je major sirijske vojske u rezervi. Kompletno kazivanje o Elezovom herojstvu na S.frontu i jednom dijelu njegovog zivota koji uistinu dojmi lahko mozemo naci u knjizi DIE BOSNIAKEN KOMMEN , od Wernera S

2007 godina devastirano mezarje

ISPUNJENO JOŠ JEDNO OBEĆANJE ISLAMSKE ZAJEDNICE U REPUBLICI SLOVENIJI-PROMJENJENI KRIŽEVI U LOGU POD MANGARTOM

Log pod Mangartom, 18. august 2007. godine

U subotu, 18. augusta 2007. godine, u organizaciji Islamske zajednice u Sloveniji promijenjeni su križevi na vojnom groblju u Logu pod Mangartom (Slovenija) na mezarima bošnjačkih vojnika koji su izgubili života u Prvom svjetskom ratu na Soškom frontu.

U prošlosti se mnogo govorilo unutar Zajednice o tome da je stotinu i pet muslimana iz Bosne i Hercegovine koji su se borili u Austro-Ugarskoj vojsci pokopanih na vojnom groblju u Logu pod Mangartom te da su njihovi mezari neadekvatno označeni. U prošlosti su umjesto prvobitnih drvenih nišana postavljeni metalni križevi. Danas je bilo postavljeno sedamdeset i devet nišana, jer su u nekim mezarima ukopana po dvojica ili trojica vojnika.

Nakon dolaska u Sloveniju muftija Nedžad Grabus obećao je da će pokušati u svom četverogodišnjem mandatu dobiti sve potrebne dozvole i zamijeniti križeve sa odgovarajućim muslimanskim simbolima. To mu je i uspjelo, 23. marta 2007. godine, kada je Islamska zajednica u Sloveniji dobila dozvolu od Zavoda za očuvanje kulturne zaostavštine iz Nove Gorice da može promijeniti križeve sa odgovarajućim muslimanskim simbolima. Od tada do danas bilo je potrebno uskladiti oblik, boju i visinu nišana koji su bili prihvatljivi za Zavod za očuvanje kulturne zaostavštine iz Nove Gorice. Slijedila je izrada nišana i svečani trenutak promjene koju je izvela grupa džematlija iz Ljubljane.

Tom svečanom trenutku prisustvovao je muftija Nedžad Grabus koji je zamijenio prvi križ i postavio nišan rahmetli Avdi Habiboviću. Tom prilikom obratio se prisutnima i kazao da je to važan trenutak za vojnike koji su daleko od svojih domova i zavičaja izgubili živote. Zahvalio se je svima koji su na bilo koji način doprinijeli realizaciji ovog projekta. Posebno se je zahvalio gospođi Ernesti Drole iz Zavoda za očuvanje kulturne zaostavštine iz Nove Gorice koja je i prisustvovala promjeni križeva. Naglasio je da bi bilo teško realizirati ovaj projekat bez njene pomoći. Zbog toga joj je u znak zahvalnosti podario sliku znanog bosanskohercegovačkog slikara Mersada Berbera.

Ovom događaju prisustvovao je i predsjednik Sabora IZ-e Slovenije g. Refik Havzija, sekretar IZ-e Slovenije Nevzet Porić, imam iz Jesenica Sead ef. Karišik, predsjednik IOM Ljubljana h. Midhat Alagić, sekretar Ureda za bošnjački dijasporu g. Muhamed Halilović i drugi.

Na kraju je klanjana dženaza-namaz poginulim vojnicima, a dženazu-namaz predvodio je muftija Nedžad Grabus.

Islamska zajednica u Sloveniji planira organizirati posebnu svečanost povodom promjene križeva na vojnom groblju u Logu pod Mangartom nad mezarima muslimana i povodom sjećanja na sve one koji su na tom području izgubili svoje živote u Prvom svjetskom ratu o čemu će blagovremeno obavijestiti javnos

Remembering the Bosnian Infantry

Fabian Bonertz

Bosnian regiments and battalions were incorporated in the joint Austro-Hungarian army since before the annexation crisis. Although stationed in other parts of the dual monarchy, their members

were drafted from the region of the Bosnian towns of Tuzla, Sarajevo, Mostar and Banja Luka. The regiments mainly consisted of Bosnians (between 93% and 96%), a large majority of Muslims among

them. In the final period of the First World War, the number of Bosnian military formations reached 10 regiments and 8 battalions.

Bosnian soldiers were mainly deployed in the Alpine theaters of the war, fighting the Italian army under harsh winter conditions and with a lack of supplies. Important areas of operation were the

Monte Meletta region in the Dolomites and the battle fields of the Isonzo/ Soča valley, which together produced more than 1.2 million casualties (The Encyclopedia of World War I 2005).

During the war, Bosnians soldiers were considered to be elite troops (Imamović 2007, p.467) and were known to show extraordinary bravery (Schindler 2001, p.70). To use the words of an Austrian battlefield guide published in 1917 by i.r.(1) officers: "Every single one a hero!“ (Stefan 1917, p.8); at the same time, they were dreaded by the Italians (Wörsdörfer 2004, p.94). Like most Bosnian Muslims during the war, Bosnian soldiers were known for their loyalty (cf. Malcolm 1996, p.159 et 163). During the late Austro-Hungarian period they attracted wide attention due to their exotic uniform which included a traditional Bosnian fez.

This paper attempts to compare the culture of memory connected with these Bosnians serving in the i.r. Army. The comparison will be between the culture of memory found in Austria itself and the

one found in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) or, rather, the one found among the Bosnian Muslims/Bosniaks. In this text the Bosnian "Muslims by nationality“ are called Bosniaks analogously to the

modern usage of the term; the only exception is the use of the word in a i.r. context (e.g. "Bosniak regiments“ as the term used to identify all Bosnians at this time).

Culture of memory exists on multiple layers and levels. Culture of memory can be understood as a term for all forms of deliberate preoccupation with historical events, persons and processes

(Cornelißen 11.02.2010). We can distinguish between individual memory connected to a personal experience, family memory and the larger concept of the collective memory of a much bigger group-- in

this case, a nation. Just like individuals can have individual memories, the theory of the collective memory assumes that collectives are able to have collective memories. A collective memory can

thus be understood as the bulk of information shared by a group. The collective memory is necessary for forming members of a group into an entity (Francois 2009, p.24 et seq.) or, in other words,

the collective memory is the glue of the imagined community.

I further believe that there is also a slight difference between individual and general collective memory, on one side, and memory as exercised by state institutions on the other. Examples of this sort include commemorations of events or sites of memory by the army or various ministries. This is obviously a form of collective memory as well, but it differs in that it is not necessarily potential glue for a nation as it is in the example of the national collective memory mentioned above. A particular kind of narrative might only matter for one particular group and not for other people or for an extended group. The German "Freikorps“ in the early twenties of the 20th century exemplify this, as they very often shared a radical narrative of events among themselves that was not completely shared by the majority of the general public or by governmental institutions. (2) However, this kind of group memory still might matter and is therefore mentioned here. The radical narrative displayed by the Freikorps, for example, became basically identical with the general political mainstream in the late interbellum period.

Collective memory needs places of memory as a center of reference. Places of memory do not necessarily have to be real places like monuments, graveyards, buildings (e.g. the Arlington National Cemetery in the case of the United States) and so on, but may also be a literary work (e.g. Mickiewicz‘s Pan Tadeusz in Poland), a legend or a myth (e.g. the El pipila myth connected to the Mexican revolution), an art piece (e.g. "Liberty Leading the People" by Delacroix for the French nation) or a historical event (e.g. the battle of Kosovo) (Weber 2011 ). Collective memory can be divided into two subdivisions: cultural memory and communicative memory, a distinction first made by the cultural scientists Jan and Aleida Assmann. The main difference is that communicative memory is transmitted orally by contemporary witnesses. This explains why something like a communicative memory can only exist for a relatively short time after the event (it is estimated about 80-100 years); cultural memory, on the other hand, has a theoretically unlimited life span and is transmitted by rituals, written fixations, traditions and so on (Erll 2005, p.27-30). The past is presented in the communicative memory as part of an individual biography, whereas it adopts an absolute and more distant form in the cultural memory (ibid.).

Collective memory and places of memory may also be part of the politics of memory, such as when a political protagonist tries to substitute historical events with myths or when memories are

influenced by political forces more generally. The politics of memory can be summarized with Hobsbawm‘s statement given to a German newspaper, "history is the material national ideologies are

made of“ (Hobsbawm 1994). The culture of memory is rather typically used for political purposes (Brunnbauer et al. 2011, p.732-738).

According to Brunnbauer, the form of the collective memory is closely tied to the community for whose identity it is important. Therefore the culture of memory is changed by the development of a

new form of collectivization within a community (ibid.). This paper will investigate these changes in Austria and BiH.

An equally important concept for collective memory is what could be named collective oblivion, but is commonly known as social amnesia. Social amnesia can "provide social cohesion on the basis of the communal organization of forgetting“ (Jager 2012, p.68). Assmann assesses that forgetting is an inextricable part of remembrance and that the fading and forgetting of memory is a normal process (Assmann 2006, p. 104-108). Social amnesia can thus be regarded as part of the concept of collective memory and can therefore also be influenced by the politics of history by volitionally ignoring an event (e.g. by not teaching about it). Regarding the dynamics of remembering and forgetting, it is worth noting that "all profound changes in consciousness, by their very nature, bring with them characteristic amnesias“ (Anderson 2006, p.204). This is why this paper tries to evaluate whether these characteristic amnesias sprung up in either Austria or BiH in the wake of changes in the national consciousness.

The aim of this work is to compare the culture of memory connected with the Bosniak regiments established in the late 19th century from both the Austrian and BiH perspectives. Regarding BiH, only the perspective of remembrance culture of Bosnian Muslims will be explored.

Graveyards (including military cemeteries) are both self-evident as well as important places of memory. Two places stick out as the most important places of memory with regards to Bosniak soldiers serving in the i.r. army. One of them is located at the Austrian town of Lebring. The cemetery serves as the burial site for the second Bosnian-Herzegovinian infantry division of the i.r.joint army. Due to the relatively large number of Muslim Bosnians interred here (805 out of 1233 Austro-Hungarian graves in total) who mostly died in the battle of Monte Meletta, this cemetery is in a prominent position and is generally known as "Bosniakenfriedhof“ ("Bosniak‘s cemetery“). The cemetery features tomb stones according to Islamic customs, as well as several commemorative plaques and a central monument honoring the Bosnian‘s extraordinary bravery heroically defending the joint fatherland. The text is engraved in German and Bosnian. (3) The Bosnian version is supplemented by a verse from the sura al baqarah. (4) This serves as an indication that the group responsible for the upkeep of the memorial site and the graveyard cares about the specific remembrance of the Muslim soldiers. The Quran verse also makes a connection to a once common German phrase about soldiers sacrificing themselves "for god and fatherland,“ as the sura 2:154 mentions those who died for god whereas the non religious part of the plaque mentions service for the fatherland. The Styrian town in which the graveyard is located is responsible for its upkeep. They receive support from the Austrian army and the Austrian war grave foundation "Österreichisches Schwarzes Kreuz." Annual commemorations are attended by the Austrian army, veteran associations, representatives from the local Islamic community, as well as delegations from BiH. At the last commemoration on the occasion of the 96th anniversary of the Meletta battle in June 2012 an Imam attended the ceremony to say prayers for the fallen soldiers ("Ein Berg als Symbol gegen das Vergessen" 2012). According to the reply to an enquiry to the embassy of BiH in Austria, the ceremonies are also attended by Bosnian diplomats on occasion. It is of further interest that the local newspaper functioning as a source for this paragraph once again mentions the bravery of the Bosniaks; the newspaper also found it noteworthy that no other i.r.regiment received more distinctions than did the second Bosnian-Herzegovinian regiment in the First World War (ibid.). Additionally, an annual "Bosniakensonntag“ (Bosniak‘s sunday) is celebrated every October in the state of Styria commemorating the service of the Bosnian soldiers. The Bosniakensonntag is a joint venture between the local authorities, military associations, three different Austrian-Bosnian friendship and cooperation organizations and the war grave commission (Stradner 2003).

The other important place of memory/cemetery is located in the hamlet of Log pod Mangartom (5) (municipality of Bovec) in the Slovenian alps.

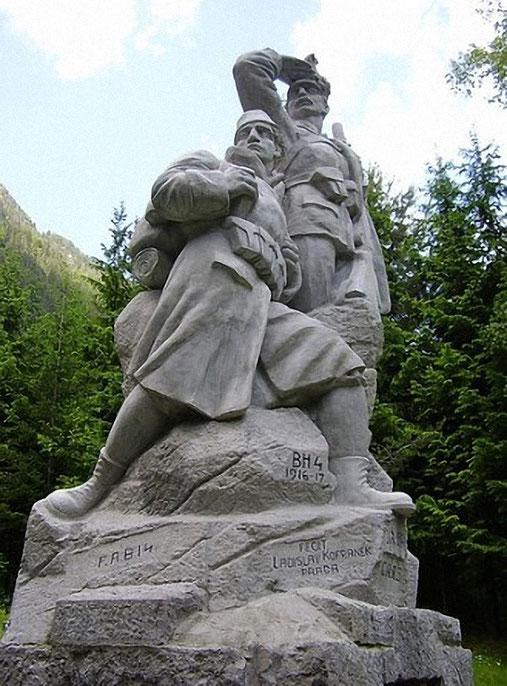

Surrounded by a scenic alpine panorama which was the scene of intense fighting in the First World War, a small i.r. army graveyard is located next to the village cemetery. The cemetery is

dominated by a monument which was erected 1917 while the battles on the surrounding mountain tops were still raging. It shows two soldiers - one Bosnian recognizable by the typical Bosnian fez

hat - looking up to the front line on Mount Rombon. A good portion of the graves belong to Muslim soldiers, as indicated by their Muslim headstones. Until recently, both Christian and Muslim

graves had crosses as markers. In the year 2005 the Islamic community of Slovenia organized for the first time a gathering and a ceremony of remembrance for the 102 Bosniak-Muslim soldiers buried

in Log Pod Mangartom. The Slovenian Islamic community was also in charge of replacing the Christian crosses with the Islamic headstones called "Nišan“ in 2007 ("JASIN I DOVA U LOGU POD MANGARTOM"

15.06.2009). This ceremony has an additional importance as the Islamic community of Slovenia is under the suzerainty of the reis-ul-ulema (grand-mufti) of Bosnia and Hercegovina in Sarajevo and,

even more importantly, most Muslims in Slovenia declare themselves as either Bosnian or Bosniak ("Popis 2002" 2002). Therefore it can be said that even though the event was organized by Slovenian

Muslim associations, it is essentially a Bosniak place of memory.

In June 2012 a monument honoring the fallen Bosnian soldiers was unveiled next to the Austrian one from 1917. The ceremony was attended by the Bosniak and the Croat members of the presidency of BiH Bakir Izetbegović and Željko Komšić, as well as the president of Slovenia Danilo Türk ("Otkrivanje spomenika u Logu pod Mangartom: Die Bosniaken Kommen Istaknuto " 2012). The event and the remembrance of the fallen Bosniak soldiers also relates to the ongoing planning of the Ljubljana mosque, which was a topic of conversation between the chair of the presidency Izetbegović and the Slovenian president Mr Türk. Mr Izetbegović also had a discussion about this with the mufti of Slovenia (Predsjedništvo 07.06.2012). The planned Ljubljana mosque is a project surrounded by a high amount of controversy. (6) Log Pod Mangartom is an appropriate place for this topic as it was the site of the first mosque in Slovenia erected during the First World War for the Muslim soldiers. A rather short report about the visit can be also be found on Mr. Izetbegović’s private website. (7)

Commemorative events are not only held by the Bosnian side, but also by the Austrian one. The organizers include the Austrian veteran's organization, the Austrian war grave commission (German: ÖSK) and private individuals interested in military history and the Austrian army, especially the army unit "Das Zentrum für Internationale Kooperationen (ZIK)“. The ZIK functions as a place of memory for the Bosnian soldiers (especially the second regiment), as it currently flies a campaign streamer (8) granted by the president of BiH, Alija Izetbegović, in 2000 (Stradner 2003) and undertook tours to the Meletta monument in Italy, the main battlefield of the second Bosniak regiment . Tours to places of memory like Log Pod Mangartom and the Meletta monument happen on a regular basis. It is noteworthy that most attendees of a commemorative event at the Meletta monument in 2011 organized by an Austrian organization of non-commissioned officers wore the Bosnian Fez ( Unteroffiziersgesellschaft Steiermark "Meletta-Gedenken in Italien" ). Similar veteran organizations concerned to such an extent with the memory of the First World War do not seem to exist in Bosnia.

The website of the Muslim Patriotic League, for example, features a section about the history of BiH. The paragraph about the First World War is, however, rather short and is mostly concerned with military history. Other topics on the website, like the events of the 1990s or the Ottoman period, have a more prominent position and sport much longer articles (cf. Patriotska Liga "I. svjetski rat" ).The section about the First World War is not yet translated into English and German versions, unlike the sections about the more modern history of Bosnia and the Bosniaks (ibid.).

An Austrian example for the institutionalized group memory mentioned in the introduction is once again the Austrian army. The cadets graduating the military academy in the year 1978 chose a badge showing the 1917 memorial in Log pod Mangartom as insignia. Just like on the real monument, a Bosnian soldier wearing the Fez can be seen in a prominent position (Bundesheer "Jahrgangsabzeichen" ). The military in this case exploits the past and the known bravery of the Second Regiment to sharpen its own modern identity; the campaign streamers mentioned earlier work very much in the same way. An informative webpage about the Bosniak regiments exist on the website of the Austrian army. (9) The Bosnian military, on the other hand, is not very active. Bosnian (military) delegations take part in small numbers in commemorative events like the ones at taking place at the "Bosniakenfriedhof“ in Lebring ("Ein Berg als Symbol gegen das Vergessen" 2012), but do not show much further engagement. A memorial to the Bosnians killed in action was unveiled at this cemetery by a general of the federation army (10) in 1998 (Stradner 2003). This shows that the Bosnian army is generally interested in places of memory for the Bosnian soldiers of the First World War, but does not show much commitment. Reasons for this might be a lack of resources (e.g. financially or personal) or tensions, as well as different opinions and different cultures of memory along the intra-ethnic lines of the now joint army of BiH.

Commemorative events in Austria are usually attended by delegates from the Muslim community in Austria (which has a large number of Bosnian Muslim members). An interesting example for a merger between collective memory and religious and national identity is the leaflet "Für ein offenes Graz“(for an open Graz), which attempts to create sympathy for a planned mosque in the town of Graz. The leaflet appeals to the concept of collective memory by mentioning the 805 Muslim soldiers who are interred at the " Bosniakenfriedhof“ in Lebring ("Für ein offenes Graz").

Due to being the former garrison of a Bosniak regiment, Graz serves as a center of commemoration of the Bosniak soldiers in Austria. The town also features a "Zweierbosniakengasse“ (Second Bosniak‘s alley) and two monuments dedicated to the Bosnian regiment (Stradner 2003 ).

Museums are one of the most important places of memory because the financier or the initiator of the museum can express his or her narrative through the exhibited objects. Museums and exhibitions

can also function as a mirror of the collective memory, the politics of memory and the general memory culture of a society or a group. Connections to the Bosniak regiments can be found in almost

all Austrian museums concerned with the topic (i.e. with the i.r. Monarchy, the Isonzo battles or the First World War). A good example is the museum of the garrison in Graz. A special exhibition

called "Die Bosniaken kommen“ was organized by the Austrian alpine society "Dolomitenfreunde“ in cooperation with the editors of a book about the Bosnians serving in the i.r.army. The exhibition

showed a large numbers of relicts of the Bosnian soldiers. The opening ceremony was attended by the high representative for BiH Valentin Inzko (an Austrian national), the Bosnian ambassador to

Austria and representatives from the Austrian army, as well as politicians from the state of Carinthia ("Blick in die Vergangenheit und Gegenwart" 2010 ).

The "Dolomitenfreunde“ are furthermore worth mentioning as they organize trips to places of memory like the Meletta monument, and a now deceased member Walther Schaumann published several books

about the Isonzo front and the i.r. military. (11)

Museums in Bosnia hardly cover the subject. The Historijski Muzej (Historical Museum) in Sarajevo only features a very small exhibition about the Austro-Hungarian period and focuses instead on the Bosnian war theater. The Muzej Sarajeva (Museum of Sarajevo) exhibition "1878-1918," located in the house in front of which the archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, has a small display about the First World War and also shows some pictures of soldiers of the unit. The rather small but nicely done exhibition seems to mainly cater to foreign tourists (or works better in attracting their attention) due to its prominent location and set up; at least, I did not manage to spot a local in eight visits.

Books are also places of memory not to be underestimated. Older Yugoslav history books narrate the story of the First World War from a Yugoslav view, focusing on the fight with the allies against the central powers (and are therefore not keen to mention South Slavs fighting on the other side) and the foundation of the state of the South-Slavs. Additionally, all ethnic groups in Bosnia have their own narrative which is, in the case of Serbs and Croats living in BiH, usually closer to the one of their co-nationals in their kin-state (in this case Croatia and Serbia) than to one of the other peoples in BiH.

Few works specifically concerned with the history of the Bosniaks have been published due to the relatively short time span between the creation of an independent Bosnia and today, not to mention the recent founding of the Bosniak/Bosnian Muslim identity itself (Hamourtiziadou 2002, p141), which was sharpened in the period after 1990. (12) The ones available mostly deal with the Ottoman times and recent history. The books "Historija Bosne i Bošnjaka“ (13) by Mehmedalija Bojić and „Historija Bošnjaka“ (14) published by Mustafa Imamović each dedicate only a few pages to the First World War and only short paragraphs deal with the Bosnian soldiers serving in the Austro-Hungarian army. Both books devote more time to the events after the First World War, like the foundation of the SHS state and the first Yugoslavia. In Austria, on the other hand, a monograph (15) exclusively dealing with the Bosniak soldiers in the i.r. army including a preface by Otto von Habsburg was published in Vienna in 2008. Another book focusing on the Bosnian regiments is the book "Die Bosniaken Kommen!“ (16) published in 1994 by Werner Schachinger. Another interesting case is a book (17) about the Bosnian infantry published by the Austrian ministry of defense in Vienna in 1971. Given that it was edited by the veteran’s organization of the Second Bosnian regiment, it is a good indication that communicative memory is usually very much alive in the recent aftermath of an event.

A small number of private Austrian and a smaller amount of Bosnian websites narrate the story, mostly from a military history perspective. There is also a small number of YouTube videos about the Bosniak regiments, mainly made by Bosnians in Austria, that show pictures of the regiment and memorial sites.

Worthy of mention is the Austrian military march "Die Bosniaken kommen," as it was composed in 1895 to honor the Bosnian regiments. It is nowadays played at almost all military events in Austria and appears to be quite popular. (18)

Conclusion

A number of differences and similarities in the remembrance of the Bosniak soldiers serving the emperor‘s army can be detected. A general pattern is that Austrian remembrance is more organized; e.g. commemorative events take place on a regular basis and are organized by a large number of different public and governmental institutions (army, local and state level authorities), NGOs (like the war grave commission) and private societies and associations with different backgrounds. Bosnian attendance at those events is much smaller and restricted to select people like Muslim army officers and diplomat. Furthermore, at the higher levels these commemorative acts often serve a diplomatic purpose and/or commemorate a special occasion (the unveiling of a monument in Log pod Mangartom and talks about the mosque planned in Ljubljana , for example, and even Alija Izetbegović‘s campaign streamer can be seen as a diplomatic gesture towards Austria). The much higher involvement of the Austrian side may not simply be a sign of more interest, but a sign of a more developed civil society and the presence of more governmental actors willing to commemorate as well as a higher level of collective memory in general. Perhaps most importantly, there could be a lack of state an personal resources on the Bosnian side. You also have to keep in mind that many more ethnic German soldiers than Bosniak soldiers fought in the Isonzo battles. Furthermore, the Austrian army is in a line of tradition with the i.r. army formation, whereas the multinational Bosnian army possesses no common tradition besides the federal army of socialist Yugoslavia. Indeed, this Bosnian army is a completely new and unprecedented institution, which had its bridge to the Austro-Hungarian military heritage destroyed by belonging to other states with an antithetic memory culture. The collective memory of the general public in Austria is sharpened by the institutionalized memory of the “Bundesheer“ as the army exhibits its memory culture in public through events like the Bosniakensonntag and various public commemorations.

It is worth noting that the remembrance of the Bosniak regiments, when originating from Bosnian Muslims, mostly takes place abroad and not in Bosnia (for example, Austrian-Bosnian societies organizing the Meletta event or the Islamic community of Slovenia erecting Islamic headstones in Log pod Mangartom). A possible explanation is is simply that the main places of memory for these soldiers are abroad and not in BiH and that Bosniaks living in Austria, when it comes to places of memory in Austria, developed a twofold identity - both Austrian and Bosniak.

A reoccurring similarity in all narratives was the description of the Bosnian soldiers as very brave and loyal. This narrative extends from the war years (Stefan 1917) to today‘s collective memory via the interbellum period (e.g. in Hans Fritz‘s book "Bosniak“ (19) published in 1931). Both the Austrian and Bosnian cultures of memory feature this narrative, which stretches out into an almost mystical and heroic area.

It can be assessed that the remembrance of the Bosniaks in the i.r. military and the First World War exists in Austria to a greater extent despite the obvious connection of Bosnia to the First World War through the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo 1914. Admittedly, this depends on someone‘s personal or national perspective. Nonetheless, in neither country does the culture of memory and the pool of shared information about the first world war extend to the level reached in other countries like the UK (e.g. The poppy appeal) or Australia, where the first world war had an immense boost for the creation of a distinct Australian identity which can still be seen by the thousands of mostly young Australians flocking to Gallipoli on ANZAC day (20) and popular songs like "The Band Played Waltzing Matilda“ (Korte et al. 2008, p.20). Even compared to the culture of memory in other countries of the region, for example Serbia and the importance of the "Albanian Golgotha“ (21) for Serbian collective memory (Clewing 2011, p.547-548), the culture of memory regarding the first world war is less developed today in both Austria and BiH as it was overshadowed by later events (e.g. the second world war).

In both cases the culture of memory is a cultural memory and not a communicative one, as the remembrance is nowadays carried via texts, pictures and traditions (like the commemorative events) and

not orally as the time frame of 80 to 100 years has elapsed.

Dedication to the topic by ordinary people (not as part of an association or a society) reaches a similar extent in both countries and is expressed mainly through media like websites and YouTube

videos. These online documents are mostly concerned with military history and usually feature the known theme of bravery and loyalty.

An aspect only to be found in Bosniak collective memory is religion. Commemorative events in Austria are usually accompanied by the local Bosnian Islamic community, and even the Bosniak events surrounding the memorial site of Log pod Mangartom tend to have a religious background or connotation. This can be explained by the peculiar importance of religion for the Bosniak national identity (Babunya, 2006, e.g. p.407,421; Detrez, 2000, p.26).

Austrian religious involvement, however, has another reason. The presence of priests of different confessions, rabbis and Imams at commemorative events is a mirror (and a relic) of the multi-ethnic and multi-religious i.r. army.

Explanations for the differential between the Austrian and the Bosniak culture of memory and collective memory include the discontinued statehood or absorption of Bosnia into different states, the recent development of Bosniak national identity and the fact that Bosnia belonged to four different states (22) since the end of the Austro-Hungarian rule-- in which the Bosnian Muslims lived among other religious and ethnic communities. The multi-ethnic, fragmented and tension-packed political situation of modern BiH makes it more difficult to establish a culture of memory (in this case). Each system imposed its own narrative of events. A specific Bosniak account of the first world war might be substituted with another account (e.g. Serbia fighting with the allies instead of Bosnians fighting for the empire) or over coated and clouded by new memories like the fight against fascism in the second world war or, in the case of the Bosniaks, the events of the nineties which had an immense impact on the Bosniak national identity (Baumann et al. 2006, pp. 29-32).The remembrance of the Ottoman times and its specifically Muslim identity is also considered crucial for the Bosniak national identity (Palmberger 2006, p.532). This strongly supports Anderson's statement that every change in consciousness brought with it a characteristic amnesia. The new narratives - alongside the aforementioned over coating, substituting and clouding - brought with them social amnesia.

The culture of memory in Austria, however, was not considerably disrupted as Austria experienced less discontinuity of the state. The only exception was the “Anschluss” but in 1938 the communicative memory still worked very well; veterans could simply tell others about the bravery of the Bosniaks. The new regime remembered the loyalty of the Bosniaks even more (Lepre, 2000, p.141). (23) Some of whom used to fight for the emperor were now "fighting for the Führer" (Op.cit, p.118). Furthermore, Austrian (military) institutions adopted the tradition of the Bosnian regiments. Additionally, a phenomenon which could be called "i.r. nostalgia“ is more widespread in Austria than in Bosnia. (24) The form of the collective memory is thus closely tied to the community for whom its identity is tied (Brunnbauer et al. 2011, p.732-738).

Furthermore, in Austrian times the Bosnian regiments and Bosnia and Hercegovina were often seen as something homogeneous ,which they were not. People from all religious and ethnic communities served in the regiments and lived in the province of BiH. This fact, of course, would be useful for the creation of a unified Bosnian identity - something which only a few in the country pursue. On the other hand, this complicates the use of the Bosnian regiments as a lieu de mémoire for the Bosnian Muslims or any other single group in BiH. Additionally and importantly, events more serviceable as a a lieu de mémoire for the Bosniaks occurred. The Bosnian regiments and the First World War are therefore simply not feasible as a place of remembrance for Bosniaks or the creators of the Bosniak nation. In Austria, they only serve as part of the military remembrance or general Danube Monarchy nostalgia.

This explains the varying extent of the collective memory and the culture of memory in the two countries analyzed; it also serves as an indication as to why the Austrian general public shows more interested in the history of the Bosniak regiments and therefore have access to a greater pool of shared information about them as part of the collective memory. The cultures of memory connected with the Bosnian soldiers in Austria and BiH are quite distinct for these same reasons.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. London: Verso, 2006.

- Assmann, Aleida. Der Lange Schatten der Vergangenheit Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik . München: C.H. Beck, 2006.

- Babunya, Aydin. "National Identity, Islam and Politics in Post-Communist Bosnia-Hercegovina ." East European Quarterly. no. 4 (2006)

- Baumann, Gabriele, and Nina Müller. Vergangenheitsbewältigung und Erinnerungskultur in den Ländern Mittelost- und Südosteuropas. Berlin: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2006.

- Bojić, Mehmedalija. Historija Bosne i Bošnjaka (VII-XX vijek). Sarajevo: Šahinpašić, 2001.

- Brunnbauer et al. "Geschichte Südosteuropas Vom frühen Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart." Erinnerungskulturen und Historiographien, Edited by Konrad Clewing and Oliver Schmitt, 732-738. Regensburg: Pustet, 2011.

- Clewing, Konrad & Schmitt, Oliver 2011, Geschichte Südosteuropas: Vom frühen Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Pustet, Regensburg.

- Erll, Astrid. Kollektives Gedächtnis und Erinnerungskulturen. Stuttgart - Weimar: Verlag J.B. Metzler, 2005.

- Francois, Etienne. Erinnerungsorte zwischen Geschichtschreibung und Gedächtnis. Eine Forschungsinnovation und ihre Folgen. Geschichtspolitik und kollektives Gedächtnis: Formen der Erinnerung:41. Edited by Harald Schmid. Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2009.

- Hamourtiziadou, Lily. "The Bosniaks: from nation to threat." Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans,. 4. no. 2 (2002)

- Imamović, Mustafa. Historija Bošnjaka. Kraljevo: Centar Za Bošnjačke Studije, Novi Pazar, 2007.

- Jager, Susanne. Interrupted Histories:Collective Memories and Architectural Memory in Germany 1933-1945-1989 . Heritage, Ideology, and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe: Contested Pasts, Contested Presents (Heritage Matters) . Edited by Matthew Rampley . Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer , 2012.

- Korte, Barbara, Sylvia Paletschek, and Wolfgang Hochbruck. Der erste Weltkrieg in der populären Erinnerungskultur - Einleitung. Der erste Weltkrieg in der populären Erinnerungskultur. Edited by Barbara Korte. Essen: Klartext, 2008.

- Lepre, George. Himmler's Bosnian Division: the Waffen-SS Handschar Division, 1943-1945. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, 2000.

- Malcolm, Noel. Bosnia A Short History. New York: New York University Press, 1996

- Palmberger, Monika. "Making and Breaking Boundaries: Memory Discourses and Memory Politics in Bosnia and Herzegovina". The Western Balkans - A European

Schindler, John. Isonzo - The Forgotten Sacrifice of the Great War. Westport: Praeger, 2001. - Stefan, Paul. Einleitung. Vom Isonzo zum Balkan Aus dem Kriegsland Österreich-Ungarn. Edited by Alois, Veltzé. München: Piper, 1917.

- Tucker, Spencer & Roberts, Priscilla 2005 'Battles of the Isonzo', The Encyclopedia of World War I, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, vol 1. pp. 587-589.

- Wörsdörfer, Rolf. Krisenherd Adria 1915-1955 Konstruktion und Artikulation des Nationalen im italienisch-jugoslawischen Grenzraum. Paderborn: Schöningh, 2004.

Online sources

- bosnjaci.net, "JASIN I DOVA U LOGU POD MANGARTOM." Last modified 15.06.2009. Accessed July 1, 2012. http://www.bosnjaci.net/prilog.php?pid=34416.

- Cornelißen , Christoph. Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, "Erinnerungskulturen." Last modified 11.02.2010. Accessed June 29, 2012. http://docupedia.de/zg/Erinnerungskulturen.

- Detrez, Raymond. "Religion and Nationhood in the Balkans." ISIM Newsletter. no. 5 (2000): 26. https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/17396/ISIM_5_Religion_and_Nationhood_in_the_Balkans.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed July 1, 2012).

- Hobsbawm, Eric. "Die Erfindung der Vergangenheit (The Invention of the Past)." Die Zeit, 09 09, 1994. http://www.zeit.de/1994/37/die-erfindung-der-vergangenheit/komplettansicht (accessed June, 12, 2012 ).

- Mein Klagenfurth, "Blick in die Vergangenheit und Gegenwart." Accessed July 3, 2012. http://www.mein-klagenfurt.at/aktuelle-pressemeldungen/pressemeldungen-mai-2010/blick-in-die-vergangenheit-und-gegenwart/.

- Österreichisches Bundesheer, "Jahrgangsabzeichen." Accessed July 2, 2012. http://www.bmlv.gv.at/karriere/offizier/jahrgang/1978.shtml.

- Patriotska Liga Bosne i Hercegovine, "I. svjetski rat." Accessed July 2, 2012. http://www.plbih.net/.

- Bosna i Hercegovine Predsjedništvo, Last modified 07.06.2012. Accessed June 30, 2012. http://www.predsjednistvobih.ba/saop/1/?cid=19914,2,1.

- Kleine Zeitung, "Ein Berg als Symbol gegen das Vergessen." Last modified June, 06, 2012. Accessed July 1, 2012. Lepre, George. Himmler's Bosnian Division: the Waffen-SS Handschar Division, 1943-1945. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, 2000.

- Statistični Urad Republike Slovenije, "Popis 2002." Accessed June 29, 2012. http://www.stat.si/popis2002/si/default.htm.

- Stradner, Reinhard. Österreichisches Bundesheer, "Bosniens Treue Söhne." Accessed July 1, 2012. http://www.bmlv.gv.at/truppendienst/ausgaben/artikel.php?id=1307

- Unteroffiziersgesellschaft Steiermark, "Meletta Gedenken in Italien." Accessed July 2, 2012. http://www.uog-st.at/Aktuell/Berichte/zwst_2_2011/uog_senioren/meletta/index.html.

- vakat.ba, "Otkrivanje spomenika u Logu pod Mangartom: Die Bosniaken Kommen ." Last modified 07.06.2012. Accessed July 2, 2012. http://www.vakat.ba/component/k2/item/836-otkrivanje-spomenika-logu-pod-mangartom-die-bosniaken-kommen.html.

- Weber, Matthias. Online-Lexikon zur Kultur und Geschichte der Deutschen im östlichen Europa, 2011, "Erinnerungsort." Accessed July 1, 2012. http://ome-lexikon.uni-oldenburg.de/54106.html.

Other sources

Bosniakische Gemeinde Graz & Türkische Gemeinde Graz, "Für ein offenes Graz." leaflet is available to the author as paper copy, the leaflet gives no further information on the year of the release of the paper.

Further recommended reading

- Des Kaisers Bosniaken die bosnisch-herzegowinischen Truppen in der k. u. k. Armee ; Geschichte und Uniformierung von 1878 bis 1918. Edited by Neumayer, Christoph and Hinterstoisser, Hermann and Wohnout, Helmut . Wien: Verlag Militaria, 2008.

-

Fritz, Hans. Bosniak. Waidhofen a.d. Ybbs: Verl. d. Druckerei Waidhofen a.d.Ybbs, 1931.

Gandini, Sigmund. Das bosnisch-herzegovinische Infanterie-regiment Nr.2 im Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918. Vienna: Bundesministerium fuer Landesverteidigung, Abteilung Bildung und Kultur, Hauptreferat Staatsbuergerliche Erziehung, 1971. - Higham, Robin, and Denis Showalter. Researching World War I History. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2003.

- Kube, Stefan. "Zur Erinnerungskultur der bosnischen Muslime.". Stuttgart: Akademie der Diözese Rottenburg-Stuttgart, 2007. Print.

- Schachinger, Werner. Die Bosniaken kommen!. Graz: Stocker, 1994.

- Smith, David. One Morning in Sarajevo: 28 June 1914. London: Phoenix, 2008.

- Stone, Norman. World War One: A Short History. London: Penguin Books, 2008.

- Susko, Dzevada. "Percepcija Bošnjačka na Zapadu.". Sarajevo: 2011. Print.

Bunkeri, pješaštva baze, pozicije i utvrde Austrijanaca i Talijana Ex Forte iz Prvog svjetskog rata

u Alpama, Dolomiti, Verona, Veneto i Friuli.